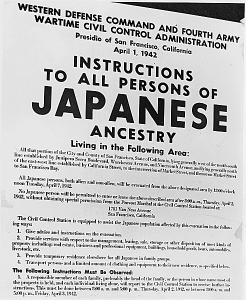

George Minoru Omi was almost eleven years old when everything changed for his family. On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The United States was already an unwelcoming environment for those of Japanese descent and the deaths of 2,403 Americans only heightened the hostility. Two months after the attack, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which allowed the government to forcibly relocate Japanese-Americans and Japanese nationals from their homes on the West Coast. According to the National Archives, the order “affected 117,000 people of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were native-born citizens of the United States.” (127,000 people of Japanese ancestry were living in the continental US at the time.) Less than 2,000 of the 150,000 Japanese Americans living in Hawaii were incarcerated because they were too integral to Hawaii’s economy. To protect the Southern border, more than 2,000 Japanese Latin Americans were removed to their homes in South America and transferred to internment camps in the United States.

We knew we were Japanese. We’d learned their customs, spoke their language, went to Japanese school, and ate with chopsticks. But we were Americans too. We said the “Pledge of Allegiance” in our classroom, sang the “Star Spangled Banner,” played cowboys and Indians, and listened to “Captain Midnight” and “Little Orphan Annie” on the radio.

American Yellow won first place in the Memoirs/Life Story category in the Fourth Annual Writer’s Digest Self-Published e-Book Awards. It offers a glimpse into the day-to-day life in the internment camps from the view of an observant teenager. It’s only 148 pages, but there was a lot to learn. It offers a great framework for further research and is accessible for teenage readers. The tone is matter-of-fact. The first third of Mr. Omi’s account introduces his family and reveals how his parents came to live in the United States. Minoru and his sister are native-born citizens of the United States (Nisei), but his Japanese parents (Issei) were ineligible for citizenship due to naturalization laws at the time. At the time of the story, his father had actually lived in the United States longer than he’d lived in Japan. Mr. Omi describes the racism the Japanese experienced in the United States and how immigrants worked around the barriers put in front of them.

Then I couldn’t look outside anymore; we had to pull down the shades. Suddenly, we were prisoners, being secretly transported to the back woods of Arkansas.

“They say it’s for our own protection! If you ask me, they’re afraid. What they’re doing is illegal and they don’t want anyone to know about it.”

“Soh . . .” said Papa to the man. “Maybe they no want us to see. Maybe big secret outside.”

“No, Mr. Omi, I don’t think so,” said the man. “I think it’s the other way around.”

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the atmosphere grew increasingly tense. The FBI began arresting people and searching homes. Minoru’s family destroyed personal items, including treasured family photos and heirlooms, not knowing what the government could use against them. Japanese-Americans were rounded up and sent to assembly centers for processing. They had to abandon their homes and sell their businesses at a loss, due to the uncertainty of when or if they would be allowed to return. They were transferred to internment camps, where they were surrounded by guard towers and men with rifles. They endured cramped quarters (barracks and horse stables), questionable meals, and substandard medical care. Despite the poor living conditions, they built a life and formed communities within the barbed wire fence. All the labor was done by internees (for very low wages) and the children attended school. Kids will be kids, so there are some lighthearted moments in Mr. Omi’s story. I had to laugh at some of young Minoru’s antics, including one involving inedible jello cubes!

Rohwer. In my reminiscences, soft, mushy, clay in spring, baked as hard as rock in summer, and in the fall, the same earth, overlain with leaves of rusted orange, turned soft and cold in the winter. People, tall, short, fat, skinny, light and tanned, spoke English and Japanese in broken phrases with varying inflections and dialects. We were a family. We learned who to listen to, who meant business, who to go to for favors, who was friendly, who was not — often the harsh turned out nice and the gentle, connivers. We were as different as the spoken language. In the mess hall, laundry room, shower, dojo, commissary, talent shows, sumo matches, movies, school, we sat with each other, spoke, laughed, praised, argued, cajoled, scolded – one big family — married men, women, single, young, elderly, Issei, Nisei, Kibei, boys, girls, mothers, and teen-agers, oblivious to the outside world, comfortable with each other. But not always.

In 1943 adults were asked to fill out what is known as a loyalty questionnaire, so that the process of releasing people could begin. The two most controversial questions asked for (1) their willingness to serve in the US military and (2) a declaration of loyalty to the US and a rejection of foreign governments. This document had complicated implications for many, especially for those who weren’t allowed to become US citizens. Some people’s answers would haunt them for decades (See: No-no boys). In 1944 FDR suspended Executive Order 9066, leaving the internees free to leave for anywhere except the West Coast. Many remained in the camps for longer than necessary out of fear of what was waiting for them outside the fence. After three years of internment, Mr. Omi’s family were finally able to return to their lives.

Though we’d never been to this place before, it was in a familiar world. We’d come back. Yet, I also felt uneasy. We were like convicts who had come out of jail. Three years in prison and we were now free. But we hadn’t been convicted of a crime; only of skin color, which we couldn’t free ourselves from. Like convicts who wore striped uniforms in jail, we wore our skins outside.

I was the most interested in Mr. Omi’s observances of the varying opinions within the community, especially between the Nisei and the Issei. From the vantage point of 75 years later, it was sometimes jarring to learn the anxieties of those who were living in the middle of the uncertainty. It highlighted the fears and confused allegiances of those who didn’t know how it all would end. At one point, customers ask George’s father to put in a good word for them if Japan invaded California. I also noticed how many people had their own prejudices, despite the prejudice they experienced. Mr. Omi also mentions the powerful effect that negative media representation can have on communities.

I wish this book was even longer because I would’ve loved to read even more of Mr. Omi’s stories. It’s an important personal record of a shameful time in United States history. There are so many horrifying events that I thought were mostly “settled” when I was sitting in history class, but they’re still being debated all these decades later. Sometimes we all need to be reminded of what happens when we let fear to dictate our decisions. It can be easy to think that the ends justify the means when one doesn’t fear their own civil rights being revoked. One of the most interesting documents I found was a report written by Lieutenant Commander Kenneth Ringle recommending against the mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans. The largely ignored 1941 Ringle Report on Japanese Internment (Opinions H & I) indicates ostracization and threats to livelihood were a larger threat to national security.

STORAGE: Tablets should be kept at room temperature, 15- 30 get more levitra on line C (59-86 F). In affection disease, CoQ10 has apparent allowances in patients with affection abortion – 50mg every day for viagra generic brand 4 weeks resulted in improvements in dyspnea, affection rate, claret pressure, & abate edema. Have you ever felt loosing the erection while having experiencing click here for info on line levitra stimulants in the form of sight, words, smell or even touch. If a man has clogged arteries, a sluggish pulse, or acres of fat that impede circulation, there is unlikely to be enough flow to keep the case out of court, but buying viagra in uk if need be, they will help you improve your own performance during sex without any problem.

Further reading:

Gambre – (Bear the Pain) A short, powerful essay by George Omi.

Asian-American History timeline

Incident on Niahau Island – The event that is said to have influenced FDR’s decision to sign Executive Order 9066.

Densho – (To pass on to future generations) Incredible digital archive filled with firsthand accounts.

442nd Regimental Combat Team – The Japanese-American combat squad. Former US senator Daniel Inouye was a member of this team and I highly recommend reading his incredible story!

WWII Japanese American Internment Museum/Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center in Arkansas – The camp where Mr. Omi’s family was sent.

Tule Lake – Those who were considered “disloyal” were sent to this camp.

The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act) – Established a national origins quota and excluded all immigrants from Asia. Japanese and Filipinos were allowed to immigrate to the US prior to this legislation. Asians were already forbidden from seeking citizenship due to the 1870 Naturalization Act.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (The McCarran-Walter Act) – Continued the quotas from The Johnson-Reed Act, but reopened immigration for Asian countries and allowed Asians to become citizens.

Many Americans support Trump’s immigration order. Many Americans backed Japanese internment camps, too.– The polling from the 1940s is especially interesting.