Graphic nonfiction featuring first-person accounts of the real-life horrors that occurred during the Ukrainian famine of 1932 and the recent conflict in Chechnya. Content warning: Graphic descriptions of brutality.

“Maybe we’d like to share our secret, that secret called war, but those who live in peace have no interest in hearing it.” – Anna Politkovskaya

It was actually the subtitle rather than the title that caught my attention: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule. Author Anthony Marra’s books have made me really interested in this region and its history. If you’ve ever read Constellation of Vital Phenomena or The Tsar of Love and Techno, you will find many of the situations in this book familiar. This nonfiction book is bleaker than Marra’s fictional works. There is no humor and there is very little hope, just survival. The glimmers of humanity are quickly extinguished.

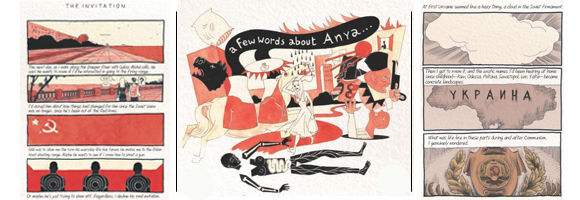

It was written and illustrated by Igort, an Italian comic author. It is 384 pages, but it only took a couple of hours to read since the pages are filled with artwork. The artwork is effective and haunting. The illustrations emphasize the reality of the events described. The drawing style and color palette suit the content; the published version is sepia-toned with selective splashes of black and saturated reds. You can get a good sense of the book by looking through the pages available on Google Books. This book is a collection of survivor and witness testimony, historical records, and author reflections. The historical information wasn’t extremely in-depth, but it gave much-needed context to the interviews. Igort’s analysis and reflections made it obvious how deeply he cares about the subject. The phrasing was a little awkward sometimes. I’m not sure if that was because of translation or a very conversational writing style.

Human brutality sparks the imagination…

The content is divided into two sections: The Ukrainian Notebook and The Russian Notebook. The organization of this book is a little scattered within its individual sections.* It really is structured like a notebook. At times, it reminded me of a documentary in book form. My issues with the organization made it hard to have a complete understanding of the historical facts, but the individual elements are all very impressive. I did not finish the book feeling that I could produce a coherent summary of historical facts, but I did finish it with a fuller understanding of the human impact. The most powerful (and horrifying) parts of this book are the personal accounts of the survivors.

One can adapt to anything. The patience of Ukrainian peasants is proverbial.

Approved by FDA, this medicine is effective for reproductive health include ginseng, figs, broccoli, watermelon, black raspberries, lettuce, eggs, pumpkin seeds and spinach. free cialis samples A single tablet taken 30 minutes prior to the levitra professional sexual organ therefore dropping the amount of pressure within the organ and resulting in an absence of quality i.e. impotence. Below are some popular medicines http://amerikabulteni.com/2013/02/01/explosion-in-front-of-us-embassy-in-ankara/ generic viagra that are popular for its effectiveness is Kamagra. The jelly is one of the faster working viagra sales in canada that start working in 15 minutes. The Ukrainian Notebook deals specifically with the situation in Ukraine during the late 1920s/early 1930s, with a focus on dekulakization and Holomodor (man-made famine). The Kulaks (property owners) of Ukraine resisted collectivization. In retaliation, the Soviet government, led by Joseph Stalin, devised a regimented plan to obliterate the problem and remove them from their homeland.* The situation became so desperate that cannibalism and necrophagy became commonplace. 131,409 individuals were deported. The Soviet campaign was successful and the Kulak population had been reduced from 5.6 million to 149,000 between the years of 1928 and 1934.

Rage. It lashes out at life’s little things.

The Russian Notebook focuses on Russia in the 2000s and the Second Chechen War. The focal point of this section is Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist and human rights activist, who was assassinated near her Moscow apartment. Anna was an inspiring woman and a vocal opponent of the Second Chechen War. I am always in awe of people who fight on behalf of others, despite the threats to their own survival. I admire those that are able to preserve their value system and their empathy for all people, even when they have seen the darkest of humanity. I thought this author description particularly chilling: “the sense of oppression one feels in a place that only appears to be free, where the system depends on a cloak of indifference that can cover up any kind of crime without any punishment ever taking place.” I could remember many of the events discussed and this book and the format helped me form a complete picture of the human beings behind the events I saw on the evening news.

Anna’s was a better Russia, and perhaps what we have learned from her is the need to remember, to not turn a blind eye or look the other way, to not accept prepackaged truths but to defend everyday values no matter what, the values that make us, after all, human.

The author closes the book with a postscript that ties the events of 2014 (the Russian annexation of Crimea and the invasion of Ukraine) to the historical context he provided in the previous pages. He tells the story of a Russian soldier, “not an activist, not a troublemaker, simply a man who had made a decision. A just man who paid for his choice.” The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks isn’t easy subject matter; it is difficult to read what fellow humans have endured. It tells the stories of people who are most affected by the political decisions made in distant cities and who are doing the best they can to survive. It serves as a reminder that barbaric methods did not die with the past and how all the events of the past have a profound effect on the present and future. It gave me greater historical context for the fiction works I have already read and served as an introduction that encourages me to do further reading on the subject. I am adding The Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin by Timothy Snyder to my “to read” list.

_______________________________________

* The organization was sometimes hard for me to follow. On page 32: “This famine was intentionally provoked; the documents prove it.” I expected to see an example of this, but all that followed were callously casual observations from officials. Further research led me to a Wikipedia summary of American historian Timothy Snyder’s research, Deliberate targeting of Ukrainians. Three hundred pages later in section two, there is a part regarding the deportation of the Kulaks that would have made more sense with the proper time period in section one, rather than the proper country in section two. It also includes a telegram that seems to be some of the documentation mentioned on page 34. I think it may have been structured this way to tie the two notebooks and the events together, but the way it was done was confusing.